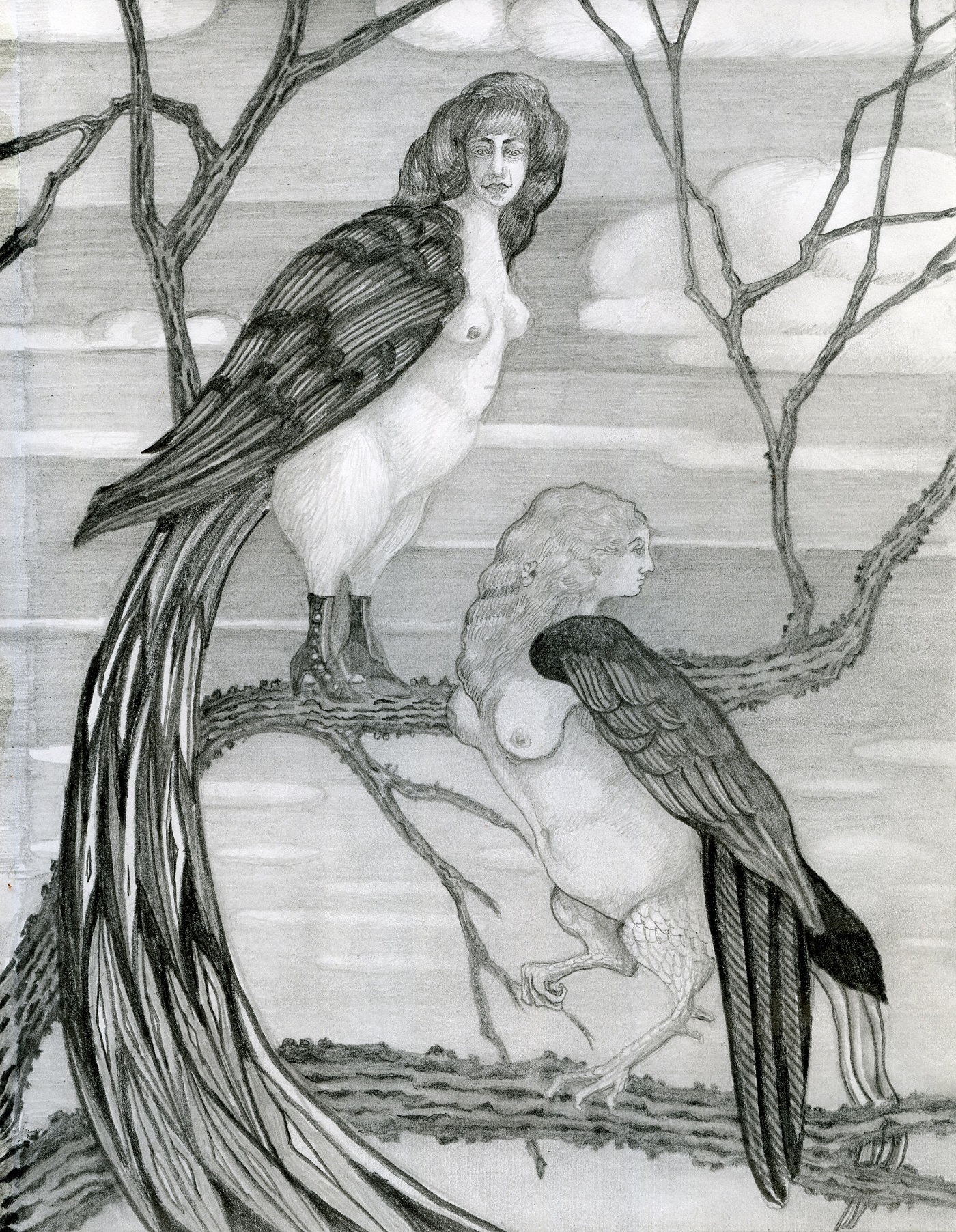

Five oh nine! A small explosion breaks the silence of a sleepless night. Was it gun fire? Or was it the crackling of paper unfolding? A cautious crowd gathers. “What is she writing?” An angry onlooker queries suspiciously. “She’s writing about us!” The woman with extra girth exclaims, and in a round about way she looks askance at her companions. A motley crew of bad memories, they fear the quiet that resurrects the past and live in terror of the stillness they find in uneventful nights. Subclinical Harpies come alive then - to usurp the peace of somnolence that daybreak does not return. Reprinted with permission from My Women, My Monsters, Finishing Line Press 2020.

In the spring of 2011, I was asked to submit some images of a mosaic “work-in-progress.” The mosaic, Subclinical Harpies, was named for a poem from an illustrated chapbook that was also in progress at the time but not published until 2020. The chapbook, My Women, My Monsters, was released just in time for the pandemic lockdowns, hence it never did see an official book-signing-party launch. It seemed that disruption was a theme that developed with this mosaic and traveled through the next ten years of accidents and surprises.

The first step in creating Subclinical Harpies, the mosaic, had begun with a surprise visit from a friend. Jill (not her real name) had a way of turning up unannounced, which miraculously always seemed to coincide fortuitously with a period bereft of pressing deadlines. So one fine spring day, while I was doing some mundane task and waiting for the phone to ring with offers of remunerative work, she came sauntering up the path to my back door.

We fell into conversation straight away – as if it had not been about a year since we had last spoken in person. We had tea with snacks and got caught up with each other’s social and work lives. I confessed that my teaching gigs had become sparse in recent weeks as also had my commission work. But I was pleased to show Jill that the downturn had some unexpected benefits. The newer, slower pace afforded me the time to experiment with new designs and products. My development of one-of a-kind musical instruments arose out of this down time. I handed Jill one of my new ocarinas – the one shaped like a partridge wing and sumptuously decorated with coral, pink, light green, and ivory colors interspersed with white gold enameling and mother-of-pearl. But when I handed this lovely instrument to Jill it slipped from my hands and fell crashing to the floor. As all good friends are apt to do, Jill apologized profusely for having somehow mysteriously “caused” the accident. I assured her that it was entirely my own clumsiness. After an awkward pause, I picked up the pieces. The ocarina had split along its length cleanly into two pieces. Jill, the perennial optimist, suggested that the clean split was an omen from a higher power and that the one-into two ceramic piece was destined for a bigger and more complex project. I looked at the two halves carefully and saw that they looked bird-like. I had been wanting to make relief sculptures of harpies, I told Jill, and these could form the basis for them. And as Jill had inspired more than one art project, I felt compelled not to disappoint her and was determined to bring pink harpies into being.

Several months later I did create female heads and feet to make harpies out of these forms. It took several months, of course, because I had to wait until I had the time and interest to make enough other small items with which to fill a kiln and not waste energy. The ceramic pieces also required two stages of firing; one for the underglaze and another for the overglaze gilding and enameling.

After the harpies were completed, I cemented them onto a wedi-board base with thin-set mortar. I also created a frame of ceramic bull-nose tiles, painted with the same pink and ivory colors found in the ocarina halves, now transformed into harpy bodies. A series of fortunate accidents made even more items available to Subclinical Harpies. My husband obliged me by letting one of his mother’s ivory Wedgewood plates slip from his hands. The pieces were made into an arch above the harpies. I broke a vintage porcelain doll gifted to me from my late mother. Their arms became the harpies’ histrionic gesturing appendages. A friend supplied me with a broken plate that had been hand painted with violet and green grapes. This formed the arbor around the arch, judiciously placed so that the grapes issued from the ceramic wine glasses on either side of the harpies. I gave the harpies hand-made tiles to rest upon that were stamped with words in ancient Chinese. The harpy on the left now rested on a tile tilted to the side which read “Life from a Swamp.” (Why? Because I hail from New Jersey, and the word for New Jersey in Chinese is “New Swamp Land.”) I made a platform for the harpy on the right that read, “In all the world there is no other.” It was a line from a favorite Beijing Opera.

As with most of my mosaic work, as the material progress continued, a narrative developed as well. The themes that grew from the work were about illusions, accidents, fragmentation, and a peculiar reference to chemical paradise. On this last reference I had another tool in my arsenal. When I had accidentally broken a tooth and required oral surgery I was given post-operative hydrocodone tablets. The extent of my post-operative pain only required using one of them so I had a whole bottle left over of these unused tablets. They were a vibrant pink and although I knew that most of this color might be washed away by the grouting process, I decided to incorporate the pills as tesserae in the mosaic. I had some compunctions about doing so. Would the message be too offensive to some people? Would addicts try to dig the pills out of the mosaic should it be hung in a public place? And what if I fell off a stool and broke my foot? Would I not end up waiting several hours in an emergency room with no respite, all the while scolding myself for not having saved at least one tablet of pain medication for this possible event? I used the tablets anyway and the pink dye was indeed washed out with grouting.

Spring turned into summer, and my Subclinical Harpies mosaic became part of an exhibition of art in a park at Piccolo Spoleto festival in Charleston, South Carolina. There it was purchased by an arts administrator and her doctor husband. I say “her doctor husband” here just to be cheeky. Everyone knows that you are supposed to say “Dr. and Mrs.” in these cases, but like my art work, I sometimes like to reverse the order of things, then step back to take a pondering look.

The public craft fair event that Subclinical Harpies was sold from was to be my last, for shortly after, it was own body that became broken. An accident and a post-viral illness left me disabled just three months later. Late that autumn, the friends who purchased the piece tried valiantly to figure out the cause of the mysterious illness. Like all honest friends, they admitted that they could not find the precise cause. That would take another five years. In that time, I sold my art fair paraphernalia, and my world narrowed to writing and drawing from the couch, the backyard, and my bed. Painting and mosaic making, like just about everything, simply took more strength than my body could offer.

I would not wish to define myself or my subsequent art by illness, yet this abrupt life change did affect and inform my art, my life, and my advocacy. It was an awakening into the world of bodily limitations, and self-conscious dependency. This circumstance also presented an unfiltered view into the tremendous holes we as Americans face in our social and medical system. While my husband was working overseas, a few good friends came forward to help me find people to do things for a reasonable fee, like clean floors, drive my car to a nearby carwash, help me shop for food in my little electric go cart, and to keep solitude at bay. I completed my Subclinical Harpies, the drawing, as well as many other drawings, from the couches and company of caretakers. What if there had not been friends? Or a spouse’s medical insurance through a state job? I had a safety net, but could easily see through the holes in it, and how tenuous life could be for so many.

Slowly, things got better with proper identification and treatment. I had a small exhibition in 2013, then one in 2014. I was able to ditch my walker by 2016. I started making ceramic musical instruments again. With precautions, I could travel again by 2018.

In 2020-2021, a pandemic era studio clean up revealed a cache of desiccated clay to reconstitute and a box of cement backer boards. My Archeological series of lost and found objects in mosaic assemblages emerged again to complete another chapter. The most important change in my final mosaics was one of scale. Instead of small figures and their artifacts, indicating a view from a panoramic distance, the new work featured objects scaled up to fit an adult’s hand, making the viewer more of a participant rather than an observer. The maker and the audience now became the occupants of a lost and found civilization.

Many of the ceramic relief sculptures in my recent mosaics were amalgams based upon museum artifacts, and the joy of being able to see these in person again after a long hiatus. Hand modeled faces, ceramic relics fashioned like old tools, locks and keys, were all juxtaposed with found objects in an assembly to create a new narrative – a journey from whole to broken and back.