Janel Spencer: In an interview with Dan Nailen for Inlander, you said that your 13-part “interconnected prose poetic collage” which you start your book off with was a new form for you. Can you speak to this process and the effect of the form on the work? It seemed to me that your use of em-dashes increased in these pieces. What were your tools for maintaining rhythm and music in the prose poems?

Rob Carney: First, I’m glad some people outside of Spokane saw that interview. That’s great. And second, the process and tools were about how to rev it up and then keep riding that momentum because the publisher at Black Lawrence Press, Diane Goettel, passed on the manuscript even though she’d just published my previous collection The Book of Sharks. Her reader told her that the last section (the opening section was the last back then) sort of faded and didn’t have the same energy as the rest. So I took everything apart, dropped all the line breaks, revised totally, created new work to replace stuff I chucked out, scrapped the individual titles in favor of starting over and working in collage, and bumped it to the beginning and think I’m better off by a long ways now. As for the em dashes, I’ve got a friend who says they’re the sexiest of all punctuation marks, but my reasons aren’t as interesting. I just use them to interrupt, or sometimes use them like a fermata in order to hold the previous note a bit longer than a comma would, or maybe they’re some vestigial tail left over from when there had been stanza breaks. But mostly I’m just using them for clauses and thoughts that stray a bit but still fall inside the main sentence. And the musicality, hopefully, still lifts the more conversational rhythm and presentation. I mean, I craft it. It isn’t just chatter. In fact, I deliberately include iambic pentameter lines so that no one can dismiss prose poetry as some lazy relative you wish you didn’t have to deal with. Maybe no such people exist, but I imagine them anyway and hate their guts hypothetically just in case.

JS: Besides the first thirteen prose poems, “21st -Century Math Exam” which is written like an equation, and the last poem, “For I Will Consider My Six-Year-Old” which is broken up into mostly single lines, the rest of your poems are written using couplets. Will you speak more on these other forms and the significance of your choice to use mostly couplets in your book?

RC: Like you said, it’s a math equation, and I’m doing it subversively and to reinforce the final line. In the case of “For I Will Consider,” that one’s celebrating Christopher Smart’s riff in the middle of Jubilate Agno where he says, “For I will consider my cat Jeoffry,” and then writes 100 lines of praise in the catalog form, so the only reasonable choice was to stick with Smart’s form for that one. And couplets? I settled on doing that years ago, almost exclusively, and as a contrast to the prose poems and list poems I also write. I like the way couplets work, with a kind of logical development and individual unity but surprises, too, and jumps or something. They’ve got an openness that solid blocks of lines usually don’t, but also a togetherness: one thought, feeling, metaphor, or image in two lines, and then again, and then again. Of course, there’s the other truth too, which is that line breaks and stanza breaks can be pretty idiosyncratic. Poets have their own ways of doing. So the questions we’re left with are 1) do their ways of doing work, and 2) can they provide sound reasons for their choices? I think I can say yes to both of those and even, should a purgatorial relapse happen, do a PhD-type oral defense that gets two-thirds of the committee agreeing that I’ve studied and know what I’m talking about, with the one hold-out vote coming from either a theory evangelist or another poet.

JS: What inspired the title for your book? When did you name it? Did any particular quote, speech, or allusion influence your choice? Did you intend it to have political or legal undertones?

RC: I had a long poem, “Facts and Figures,” and it seemed to me like the title poem, especially because it could also lend itself to two of the book’s section names and also blend well with the “13 Moons” section since so much of the poem is about a space expedition. As for when exactly, I’m not sure, but I didn’t choose it last. I mean, it’s not like I had all 41 poems done and just had the book title left to decide on. It was sometime midway through, and having the idea of the larger arc, the whole of it, helped me to fill in the gaps and write the remainder.

JS: Would you talk to the significance of place and numbers in the book? For example, what is the significance of thirteen? Is it alluding to superstitious beliefs and/or Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” both, or neither? What do you think is the significance of thirteen in Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird?” Are our numbers as arbitrary as our students fear they are? (“In 623 words, explain your reasoning…” from “Fact 13”). Are they significant? Or to what degree?

RC: I can’t speak for Stevens but imagine he thought “Thirteen Ways” sounded better than “Twelve Ways.” “Thirteen Ways of Looking” has better rhythm, a run of three trochees. Also, the poem feels somewhat mysterious, so maybe superstitions about the number 13 add to that. Myself, though, I liked 13 because that’s how many moons there are in a year, and I had the poem “Thirteen Moons” already, so in shaping the three larger sections, I decided to have 13 pieces in each. That made sense to me, and making sense is important. Take Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”; it’s in 52 sections rather than an even 50, and maybe that’s to match the number of weeks in the year, like people would spend a week with each section, spend a year with the poem, you know? I can’t prove that, but it seems right. As for the line you’re asking about—”In 623 words, explain your reasons why”–that’s because “Fact 13” has exactly that number of words in it according to my computer’s word count tool. It’s a weirdly specific number, not the usual 500 words or 1,000 words of most essay assignments you get in school, and I felt like it was a lucky detail that 6 ÷ 2 = 3. No one cares but me, I’m sure, but I thought that was cool.

JS: In what ways is this newest collection unlike previous collections of yours? What echoes can be felt across your collections?

RC: I’ll start with the echoes because I think my voice is my own and also the thing you’ll hear in all of my books. The subjects, moods, forms—those things always change, but my voice is there whether I’m working in long forms or short, sonnets or prose poems, creation stories or lists. And each book, I think, and hope readers agree, is well structured. Julie Wade, for instance, wrote a lot about how I structured 88 Maps (Lost Horse Press) in her review of it for The Rumpus, and I was glad because it meant she appreciated the work I put in on that. I think about a book’s entirety, start to finish, so it’s nice when someone smart notices. That said, I don’t want to repeat myself from one book to the next. I want each to be unlike the others since otherwise I’d be too bored to do the writing. Readers too; they’d be bored. There’s got to be surprise even if the surprise is to find myself writing an actual sequel poem. That did happen this time. I have a poem in my first book, Boasts, Toasts, and Ghosts (out of print), called “If I Hadn’t Drowned in My 30s, She Says, Today I’d Be 73.” The “she” in the title is a woman named Madame Kafelnikov, and now she’s back, this time in a poem titled “Best Healing Witch in Louisiana.”

JS: It seemed Jack Gilbert’s influence was evident in “Fact 3” and “Part Moon, Part Wing, Part Spark.” Would you agree? Who do you consider your literary heritage?

RC: Well, I appreciate you saying that, but no. I don’t read his work much even though I ought to. I feel more drawn to poets like Robinson Jeffers, Anne Sexton, Richard Garcia, or to individual poems like “The Elements of San Joaquin” and “Final Solution: Jobs Leaving” by Gary Soto and Simon Ortiz. I like Frank O’Hara. I like Frost. There are Eastern European poets, like Vasko Popa. I’m not sure I can use the word “heritage” exactly, but if I was a recess captain picking sides for poetry kickball, I’d pick them. I’d want to be on that team.

JS: Your poetry works against readers’ expectations in a playful way. In “Thirteen Moons,” for example, you finally address a blackbird (alluding to the one Stevens taught us to look at it in thirteen ways); however, in your poem, one of thirteen moons is being thrown at a blackbird, and the bird is the one looking at the moon: “One [moon] she threw at a blackbird… / watching from the doorway.” When you talk about Galileo, you talk about his love story with a neighbor (made up or based in truth?). In “When a Black Cat Crosses Your Path,” you immediately play against expectations by answering the ominous title with the first line: “it means you’re probably in a neighborhood.” Would you speak on your use of the element of surprise in your poetry? How do you develop it?

RC: I dig this question, thanks. Taking things in reverse order, what I liked about the first line of “When a Black Cat Crosses Your Path” was that I thought it was funny. Thinking of that line made me smile, which I took as a good sign. And I liked that it led me to wonder what would happen in the next lines. Turns out the thing that happened was that I just followed sequential logic: “When a narwhal crosses your path, / it means you’re in a boat.” And then I could proceed from there. The nice thing that happens sometimes is that stating the obvious is the last thing anyone’s ready for, and it can be oddball funny and a good hook. Now, the Galileo poem that you asked about—is it a made up story or based in truth?—I like to answer questions like that this way: Yes, it’s true, except for all the details. But I’ll add to that just a little and say, to me, the key lines are about their need to be close but apart because so many people seem to take joy in spying on and gossiping about others, hoping to ruin what others have. Like they think their own lack can be filled that way. It sucks, but it’s true, and it makes sense for that idea to appear in a poem about discovery and wonder versus denial and suppression. Now, about the blackbird in “Thirteen Moons,” you’re right, though I hadn’t thought of it in terms of Stevens until you asked me. The girl has a chance to see herself from an outsider’s point of view and be less careless about her actions and the effect they have on others, but she shoos that away. She doesn’t want to look at herself thirteen ways, or even two ways, because she’s beautiful and knows it and is used to feeling free to be a taker. But to come around again to your question about surprise, I only borrow from the Goldilocks story. My ending is different and not about the girl—she’s parachuted home—and not about the little bear either. It’s about the father bear seeing his son’s hurt and knowing that a future full of more hurt is out there. He can’t, no matter how much he wants to, protect his son from loss and sadness.

JS: What, for you, is the power of personification?

RC: The same power, probably, as there is in animism. People need their wildness back. Using figurative language to evoke the animal in us seems like it ought to be one of poetry’s jobs. Jeffers does this. Mary Oliver does this. My friend Scott Poole does this sometimes—he and I have a new book coming out in August called The Last Tiger Is Somewhere (Unsolicited Press), poems by both of us—only Scott’s way is more often Absurdist or funny. Anyway, personification is just the other side of the coin, right? Personification is helpful because most people need to, as Jeffers says, “uncenter our minds from ourselves” and “unhumanize our views a little.” People aren’t good at that, so personification is a tool to help show us how non-human things are like us, and then maybe that leads to feeling and understanding and valuing. At least I hope so.

JS: I greatly admire children’s authors, and your writing reminds me of the imagination and creativity of the talented JonArno Lawson. Have you ever considered writing poetry for children?

RC: Heck yeah, I’ve considered it. In fact, I have a book—maybe three—coming out from the children’s book imprint of Nomadic Press (Little Nomad). I don’t know the details yet. I got an acceptance that told me they’d be back in touch with the particulars and to be patient, so I’m being patient. And I have another one I think could be great with the right illustrations. It’s called “What Would You Do with a Mini Canoe?” If anyone reading this is a children’s book publisher, please reach out and we can go from there.

JS: How did you learn about the publisher Hoot ‘n’ Waddle in Phoenix? What made you decide to publish/submit your work to them?

RC: I learned about Hoot ‘n’ Waddle by accident. I’d sent it to Four Chambers Press (“The Heart of Literature”) and got a good news/bad news letter back. Four Chambers was in Phoenix, and “was” is the bad-news part because they said they loved my book, wanted to publish it, but were going on a maybe-forever hiatus. So they suggested I see if one of their editors, Jared Duran, would want it instead since he was branching out from his Limited Engagement podcast series into book publishing also. So that’s what I did.

JS: How has life changed for you in 2020? Has it inspired more writing? New myths?

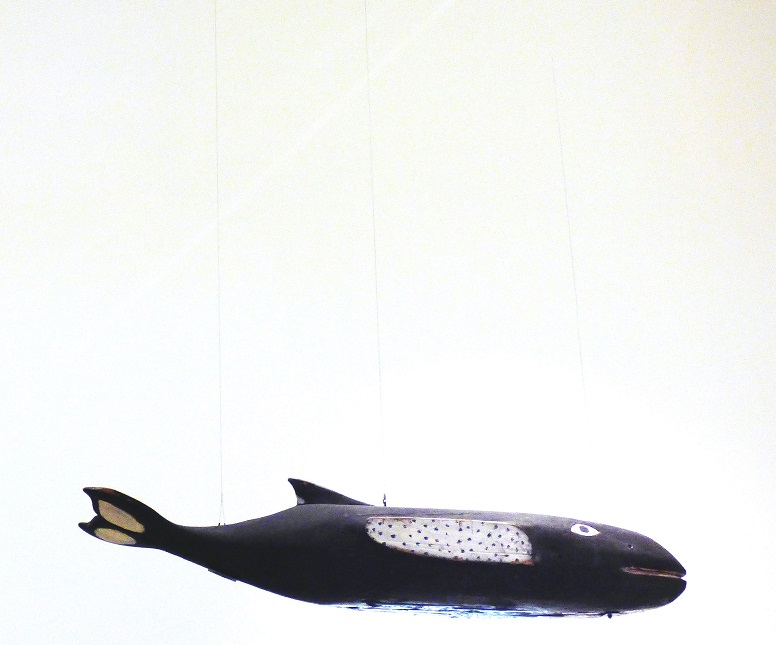

RC: I miss going places without disease fears. I miss being in restaurants. I feel ground down, eroded, and then hollowed out into a dry well I have to yell and echo from the bottom of because Trump and Barr and McConnell and the horrid rest of them are always in the news, and with our lives at a stand-still, the days until they’re gone feel so much slower and longer. But the rest of your question is a nice break from that mood. I have a new myth called “Why We Have Pelicans” coming out at Terrain.org sometime before the end of summer. And my book of 42 flash essays titled Accidental Gardens (Stormbird Press) kept me busy during May with all the pre-publication work, including writing some extra content as an exclusive for Stormbird readers, which turned out well, I think: an essay-poem-hybrid called “Cetology vs. Anthropology.” My mom is the one who gave me the idea. She asked me back on Mother’s Day if I’d heard about the white orca in Puget Sound. I hadn’t, but it’s a whole lot better news than the news coming out of DC. My mom sent me an orca, so to speak—a really rare one—right when I needed an orca. How nice was that?