Having known Kayla Rodney since we were in the MFA program at San Diego State University together, I have admired her use of vocabulary and diction to elevate the poetic aesthetic of a work since we were in Ilya Kaminsky’s translation class in 2014. Take her translation of the beginning of Azzurra D’Agostino’s first untitled poem from Canti di un luogo abbandonato (Songs of a World Abandoned):

Here, a field flanked farmhouse

with chameleon colors is still

thought lifeless by those who never heard

the sounds that proved otherwise:

the dog in the yard, scampering mice,

a song,

a motley ravenous crowd of men and beasts

things that are all phantom now.

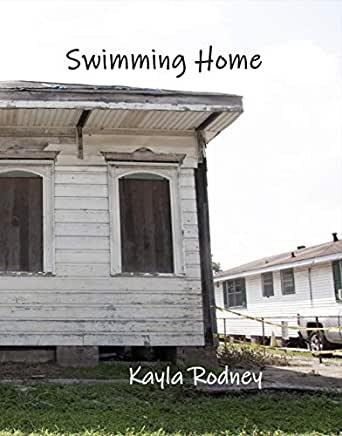

Her talent with diction, music, and the lyric is apparent in her first collection of poems, Swimming Home, which begins with a grocery list (“Making Groceries,” p 1) that very quickly becomes much more than a grocery list, transforming seamlessly into a list of “home” (which for Rodney is New Orleans), and all the ingredients that make it home. She recalls the ingredients like an incantation to the magic of memory:

-two day old French bread for pudding

…

-gumbo boils over tops of pots, splashes onto stoves with roux dark as Mississippi water

…

-the Creole queen whose blood is the history of the victor, mama, passé, daddy, paper bag brown

…

-black bodies bump like logs in the flood water

…

-bullets fall down like ash on Pompeii

…

-the bom bom bom of open palms on congo drums in Congo Square, dirty chained feet dance in the Africa of their psyches

…

Tender moments, family, and voices recorded straight—in dialect—breathe life, beauty, and truth into her collection, which becomes an ode to who she is and all who have aided her on her own hero’s or heroine’s journey.

Black mamas and daughters on their porches.

from “Tenderheaded,” p 3

…

Mama that hurts!

Hair yanked up and brushed flat into barrettes

then twirled around fingers making perfect water curls.

Between these sweet moments, Rodney uses her authority to speak on injustice against Black communities, historical and current:

Little white boys play with toys

that little black boys…can’t.

…Black mamas stand on porches

from “Musing from the Condohood:” p 5

like lifeguards presiding over the sea.

The richocet of raindrops hitting car tops

echoes through the projects.

Children play in puddles and potholes

while mamas yell about getting out

of the rain.I look towards the sun

from “Raindrop Symphony,” p 20

wondering why the devil beats his wife.

In “Black Holocaust,” she weaves current, historical, and literary allusions (invoking Langston Hughes) and strings a symphony with anaphora and alliteration to give the poem its full and necessary emotional weight worthy of its title. The title is successfully argued with undeniable and horrific evidence.

…

p 22

hung by the neck I can’t breath, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.

Kerosene rains and ignites fire beneath my feet.

…

Black bodies piled up in prisons.

Black bodies piled in projects like rats.

Black bodies piled on street corners like crumpled coal.

Black bodies wading through the waters of your consciousness.

Black bodies trying to figure out how we too can sing America.

One cannot grieve loss fully without having experienced love. As much as the book mourns historic and current loss within Black American communities, it also honors love and celebrates Black bodies:

Coffee skin glows in the dark

from “Tangled,” p 11

I drink it like I need to wake up.

Rodney is a big fan of Greek mythology, and her book explores Homer’s tale of The Odyssey and characterizations of the goddess Calypso in particular. She ties this mythic story and her versions and retellings with the natural disasters, the hurricanes she’s lived through while living in New Orleans as well as watched with held breath while studying in other states.

I

from “Snow Globe,” p 29

from the dry land of Texas

a glass of water in my hand,

watched my city drown away

as if the debris filled commemorative globe

in the gift shop

reading 8/29/2005-8/29/2015

was given a shake.

In her collection, God is as He is in the first testament, and as the Greek gods were—foreboding, destructive, and to be feared:

I am paralyzed by the eye of the storm

hovering above me like God’s mouth.Open so wide as to swallow me whole.

from “Mouth of God,” p 8

This God is insane

Untitled, p 27

doesn’t he know that flooding

the earth expecting

different results makes him a

mad man, obsessed with the rain.

Even God in her book, however, can’t resist the gifts of New Orleans:

God likes his gumbo

from “You Can’t Crawl out of a Bowl,” p 31

full of music notes and Fleurs de Lis

cobble stone streets clacking

with the sound of hooves,

Mardi Gras bead filé to

thicken the rue.

And through it all, Rodney is prepared to love, sing, laugh. She tells her story with humor and wit.

At the front door,

from “Witness,” p 39

the hurricane is knocking,

screaming about our Lord and Savior

Jesus Christ, with some informationals

for me to mull over.

She creates her own myths in which she demands more for herself:

Because I stick one foot in the Atlantic and the other

in the swamps on an alligator’s shoulder blades.Because I turn the moon in its socket and leave it there,

from “Why I Deserve a Raise from Apollo Who Has Decided That He Wants to Go on Vacation in the Poconos,” p 51

seeing as no one has space for both the moon and the sun

in their bedroom, I am asking for a raise.

Along with her own voice, she includes voices of those who also want and would demand better for themselves and their community.

I’dda said

Untitled, p 54

da world is worse na dan it was den

before dah storm.

Her brilliant interweaving of mythic, cultural, as well as biblical references build to allegorical questions about the importance of home. First, she addresses the seduction of leaving home, of exploration, of the excitement of discovery that Odysseus felt with Calypso, and in doing, brings in the nuance of desire and fate, or what is beyond our control, what compels us on a certain path, in all our journeys:

smell your ocean hair

from “Odysseus to Calypso,” p 12

with its clicking shells

and baby starfish barrettes

…

I would have stayed a million more years

but restless feet

and an incomplete journey home

drove me to the water.

What does it mean to return home changed? After a period of time? What does it mean if your only means of returning home is via the imagination, however much you desire it?

This theme of home and diaspora is particularly resonant in our current national and international climate, during a pandemic, global warming and quarantine. It is a theme that drives the author, drives Odysseus home, drives the writing, and drives each of us, ultimately, as we chose or are forced to chose to create places, homes, and homes away from home, where we will return or stay, or eventually say goodbye to forever.

I left the south for the west

from “Passé Blanc,” p 48

and browned, a sugar-sprinkled pecan.

…

I rub my skin and it’s like touching mousse.

I ask Africa to take me back

and she tells me I’m too far gone

but I can always visit.

It is an important time for reflection, for revolution, for self-discovery and for coming back to what is most important. Thank you, Kayla Rodney, for taking us home with you, even if just for a visit, and on a part of your journey.

Read an interview with Kayla Rodney about her book Swimming Home here.