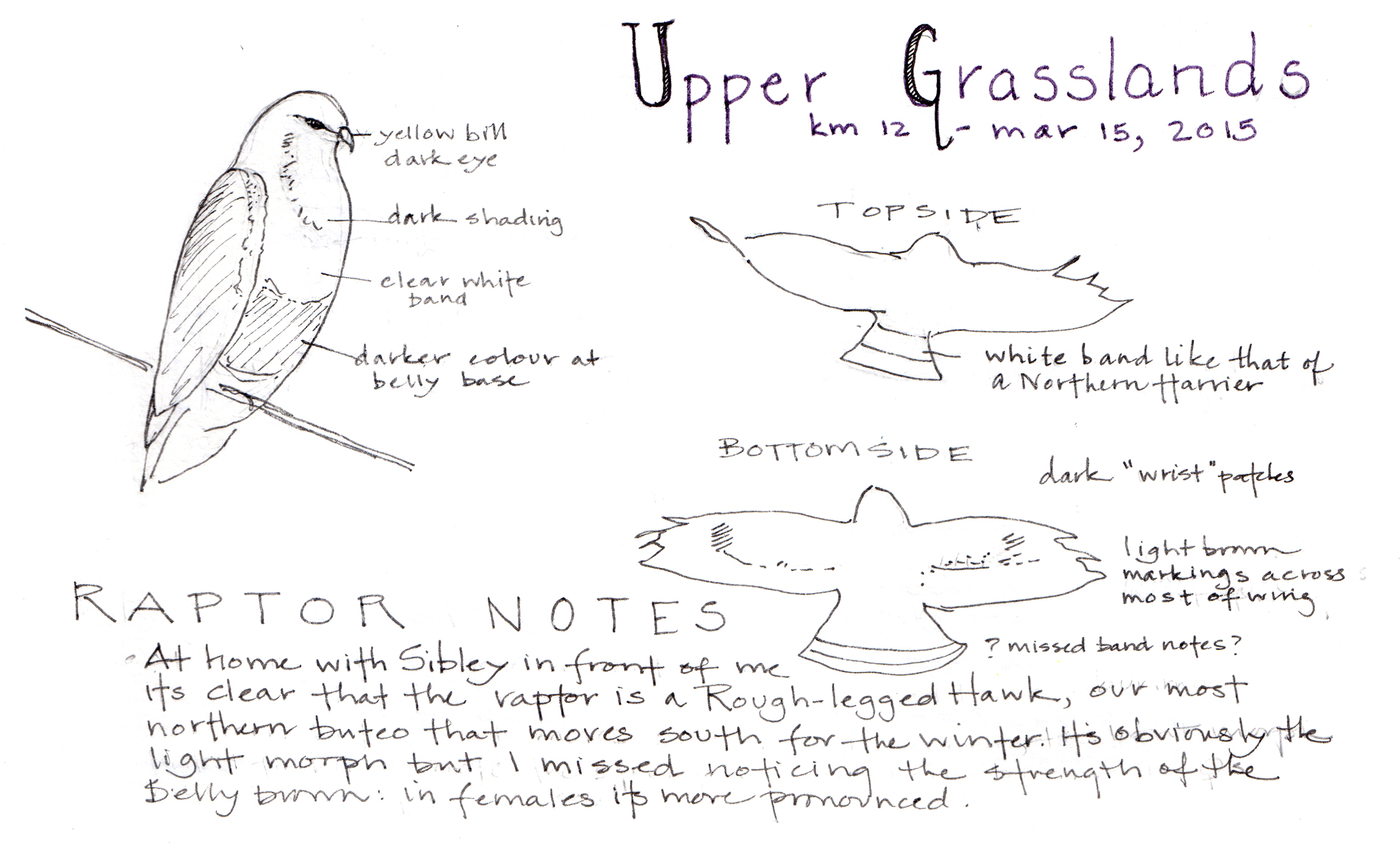

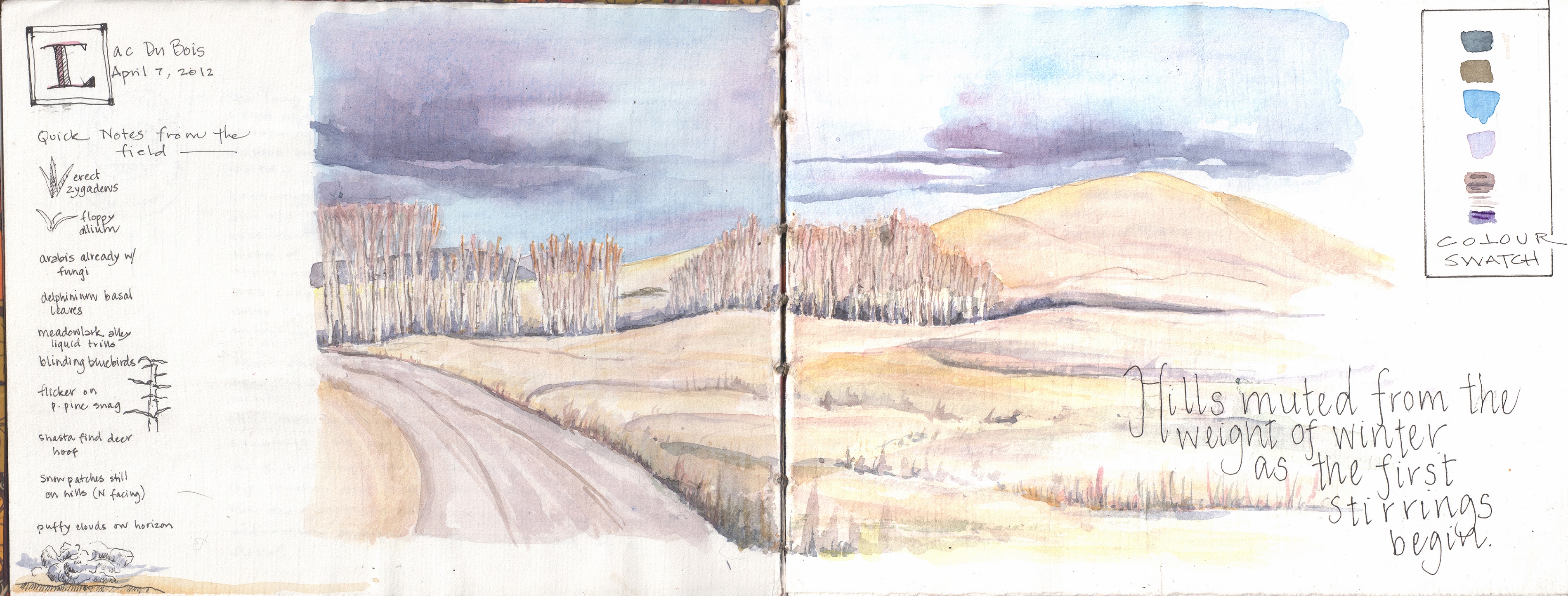

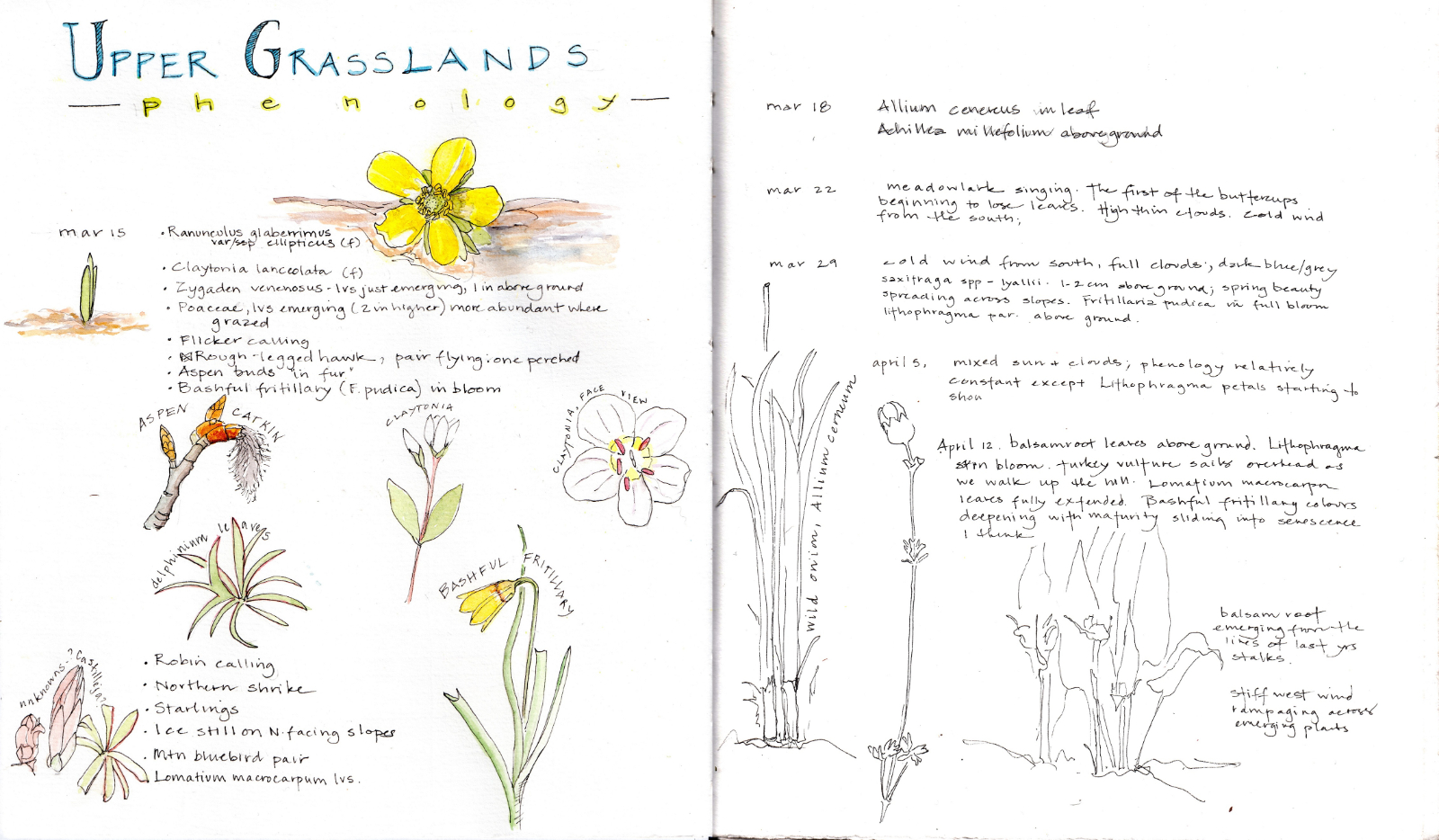

On a Sunday afternoon in middle March, I open my truck door and step into in the high, thin light of a spring afternoon in the upper Lac Du Bois grasslands, just north of Kamloops, British Columbia. Around me, the hills are brown and muted from the weight of winter. I’m layering up—hiking boots, pile, windbreaker, knit cap, gloves, binoculars—when my eyes drift skyward. There, perched on a whip-thin aspen, a raptor stares down at me. I reach back into the truck, one hand scrabbling for field journal and pencil even as I bring binoculars to eyes. Knowing that my time with this bird will be shorter than I’d like, I make notes as fast as I can, willing my body to be a conduit: eye-brain-hand-page. The bird faces toward me: lighter than a red-tail hawk, clear white belly, speckled breast band, dark tail, dark mask on its face circling down to breast. As its head swivels away and then back, a hooked bill (maybe with black at the tip?) flashes past. Then it’s aloft. Broad wings, clearly a buteo and not a falcon. The bird cants through sky, a white band slicing across its tail, until the nearby hill swallows it whole. My pencil stops. Silence holds.

And then, the starlings across the road chatter the day back into sound. Time regains its normal footing. Crossing the gravel road—headed towards the small, unnamed body of water that my students and I call Botany Pond after the discipline that brought us to it—I think about the moment I just shared with the hawk. I am different after I have felt a raptor’s glare skittering across and then dismissing my form. But even now, years after I first learned to hunger for such moments, I can’t predict their occurrence. Other than putting myself in place, field journal in hand, I can do little to facilitate them. What I do know is that, in the Age of Humans, the Anthropocene, collecting these moments feels like a kind of hope.

Collections are often defined as ‘groups of things’: plastic figurines, plant specimens, or poems. Beyond this, the limits of collecting, and by inference, of collections, are surprisingly contentious. Some argue that collecting is a basic part of the human experience, a remnant of the foraging instinct found in all animals, and includes any gathering of objects. Collections, these experts argue, can be amassed without direct intent, with a significance, if any, understood long after their initial collection.

Others insist that collecting includes only the deliberate gathering of ‘things of subjective value.’ Among those collections made with intent, some may be temporary, destined for one season; more aspire for permanency. Nearly everyone agrees that diverse motivations prompt our collecting: a way to pass time, a quest for wealth or knowledge or status, a salve for a childhood hurt, a pathway into the past.

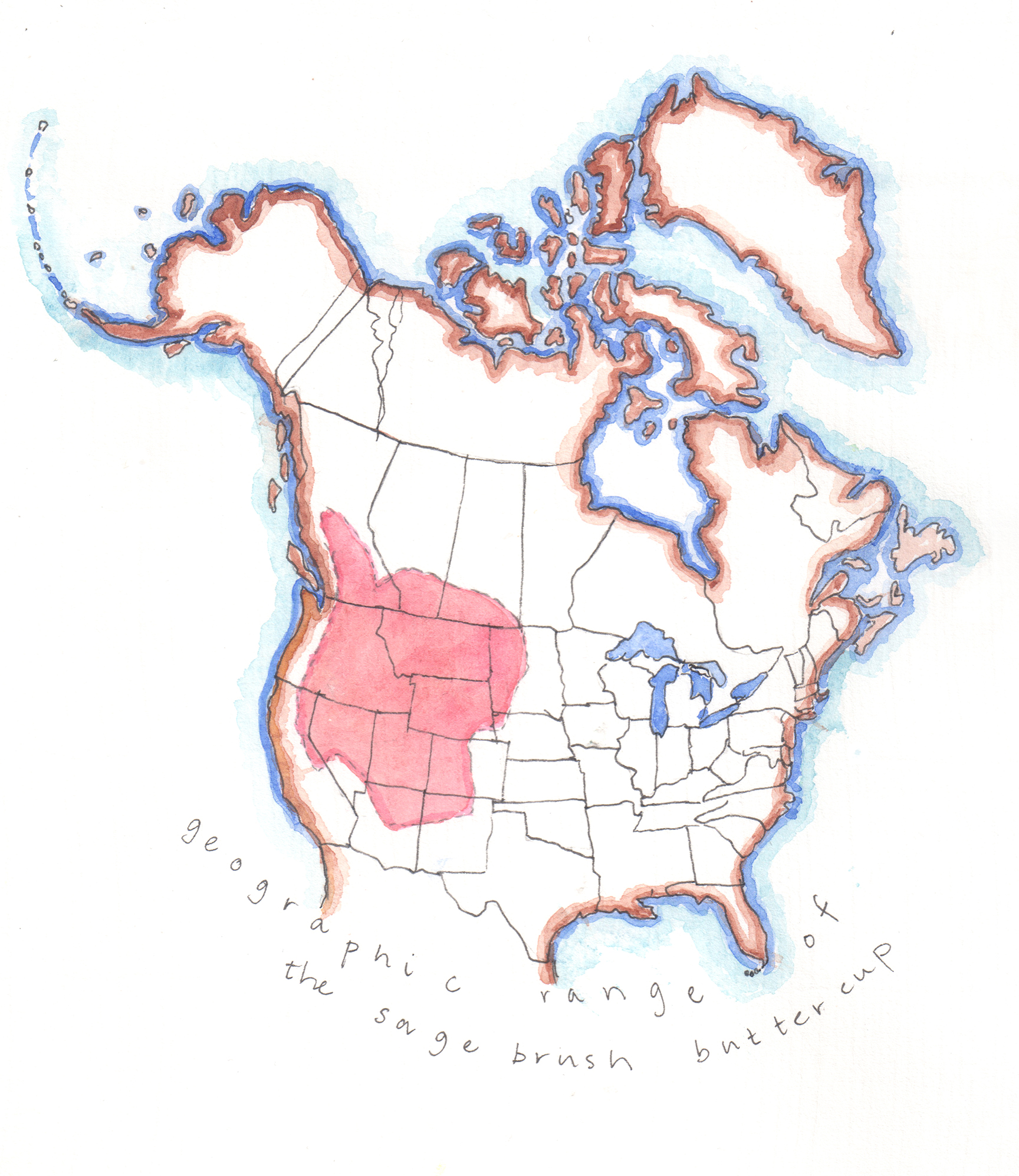

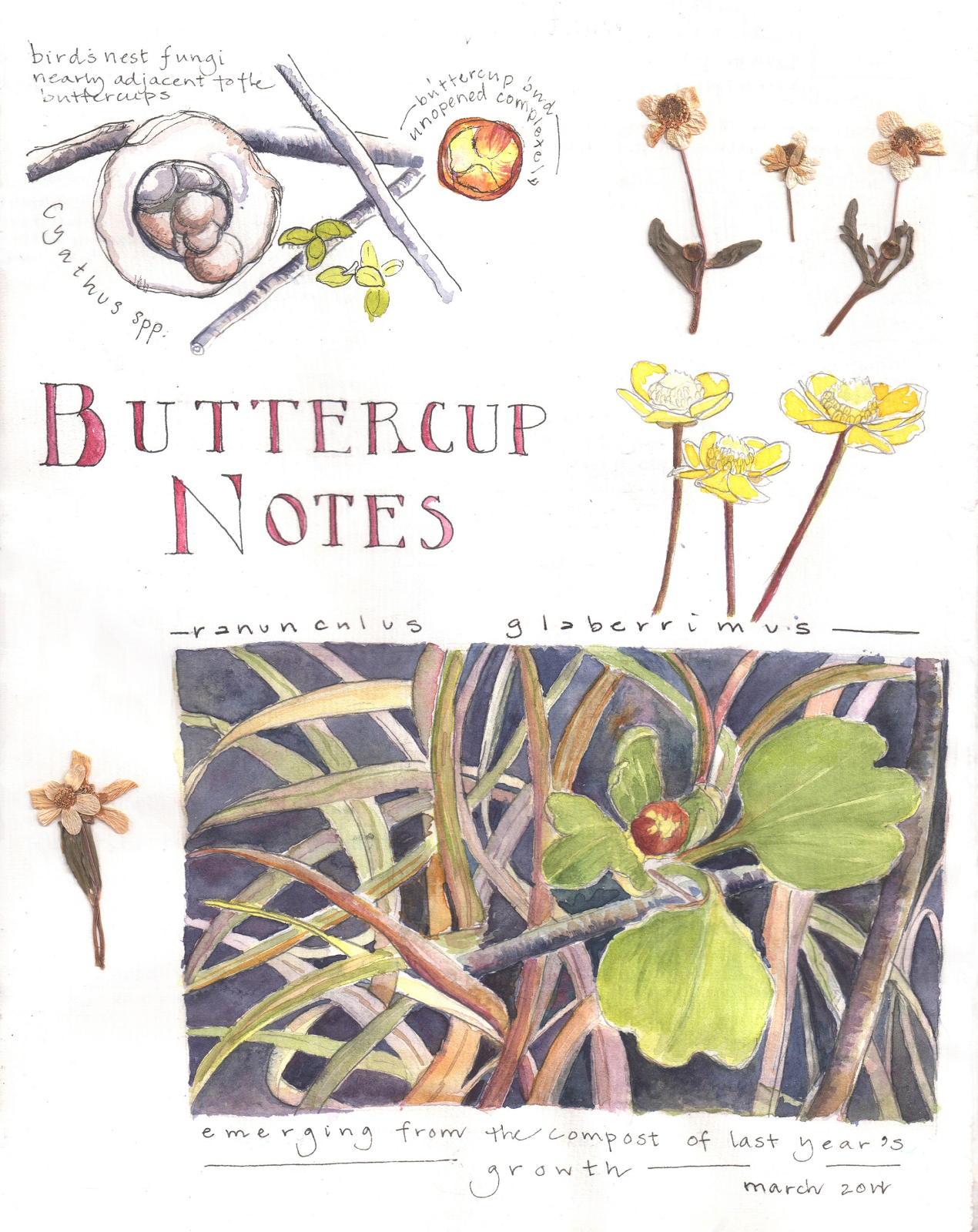

Yesterday, my research student Dominic and I spent the morning counting the number of sagebrush buttercup flowers in our plots on the hills just south of Botany Pond. The dataset we tabulated in a Rite-in-the-Rain field book is good; it’ll add to our understanding of this species’ phenology. Yet, even as we shook and shivered beneath passing snow squalls, I understood we weren’t collecting numbers alone. Last year, during unseasonably warm temperatures, I found sagebrush buttercups blooming in November. A whole hillside: five months too early, a full season out-of-sync, a yellow flag of the Anthropocene’s growing unpredictability. After a winter of worry, yesterday’s data set reassured me; today I woke wanting more.

Collecting is rarely without risk. To both the collector and the collected. Sagebrush buttercup’s scientific name, Ranunculus glaberrimus, is based on a specimen collected near Kettle Falls on the Columbia River, by the Scottish plant collector David Douglas. A collector who lost his life, rather inexplicably, in Hawaii while travelling home from his third collecting trip to North America. In the grasslands throughout the intermontane West, sagebrush buttercups root in place, entangled with soil bacteria, pollinators and seed dispersers. In the herbarium of Kew Gardens, the buttercup specimen Douglas collected—its dried carcass, flattened and glued onto an individual sheet of paper—stacks among other specimens in a metal case. Inert, but intact, for nearly two hundred years. “Objects,” writes Susan Stewart in her book On Longing, “are naturalized into the landscape of the collection.”

It’s hard for me to imagine the determination of botany’s most famous collectors; yet I know many of us work long hours to collect, and sometimes preserve, ‘groups of things.’ In his book, Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari writes, “Over the course of his or her life, a typical member of a modern affluent society will own several million artefacts—from cars and houses to disposable napkins and milk cartons.”

If we all collect, the question, of course, is what collecting, what collections, do we want to most shape our lives?

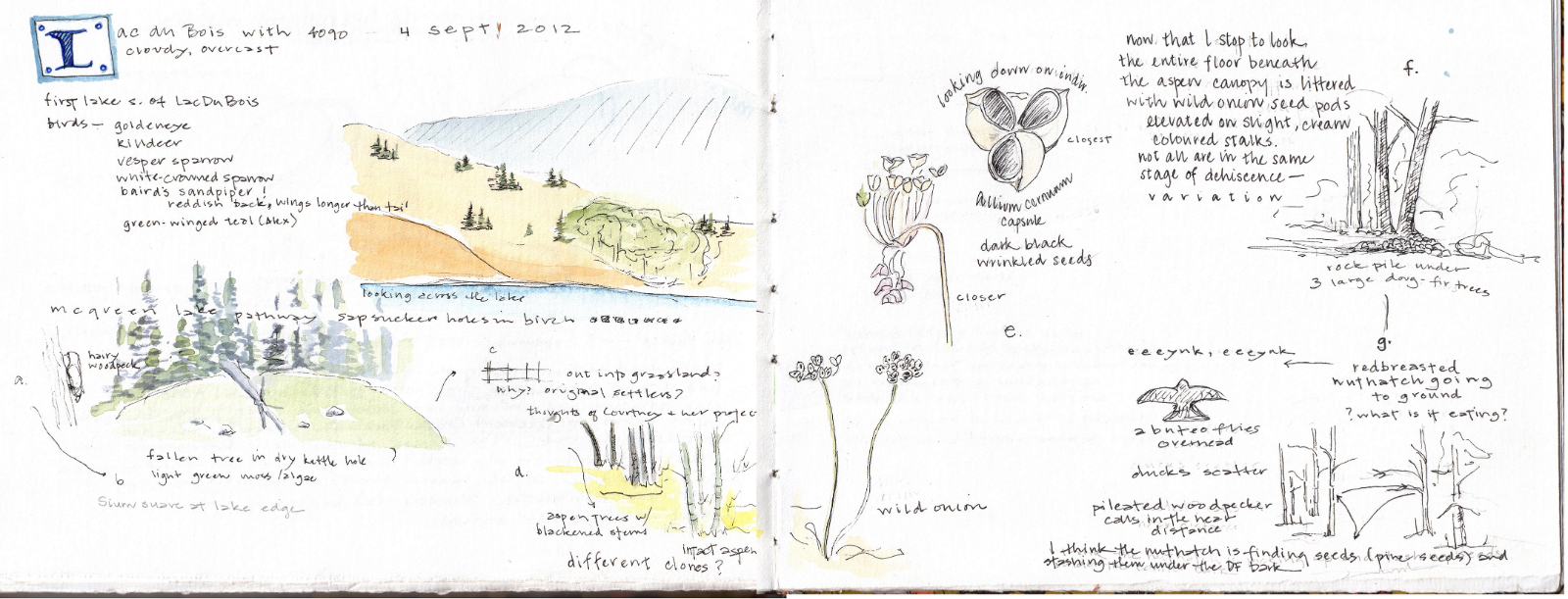

Walking past the buttercups that we sampled yesterday, I know that I will spend the rest of the day hunting for more moments like the one I shared with the hawk. If I’m lucky, I’ll walk back to my truck with a few pages of sketches and notes in my field journal. I’m not doing anything new. As a tradition, field journals—often containing both images and text—have deep roots in botany. And much of what I will observe has been already noted by others. Like most places in our world, this grassland has been imaged by satellites I can’t even see. Other devices—trail cameras, iButtons, geolocators, PITT tags, RFID readers—collect yet more data nearly year-round. As one of BC’s few protected grasslands and one that is located less than 20 kilometers from the university where I teach, this place has been poked and prodded by scientists of all stripes. Quite literally, I could suffocate under the weight of paper printed with facts others have learned about this place.

Even though I’ve walked more often at Botany Pond than any other place I can name, I wonder how much of what I know about this place has been gathered second-hand—read in scientific journals or off a screen. Does it even matter if I collect my own stories of place? In his biophilia hypothesis, E. O. Wilson argues that humans are biologically predisposed to pay attention to the natural world, but most of us are too busy, too nomadic, to develop strong relationships with it.

Maybe that’s what makes my first-hand collecting at Botany Pond, field journal in hand, so compelling. This is learning unplugged, free-range. No confining disciplines, no guiding commentary, no guaranteed outcomes. This is a collection built not from the passive observations I make hiking with friends, but from an ongoing, active dialogue with the world. Today in Botany Pond, hawks soar and sagebrush buttercups bloom. Last year, not far from here, I watched a red-breasted nuthatch make repeated journeys between the ground and a Douglas-fir tree. Collecting that moment in my field journal transformed a momentary curiosity that might have been lost into my own independent discovery of

nuthatches’ seed-caching behavior. Imagine my glee when I returned home and found reports corroborating my interpretation.

Any field record attempts to translate the complexity of the natural world into a recognizable order. How I collect my observations, however, influences what I observe. Drawing, with its emphasis on seeing, never allows concrete particulars—the weight of a bird’s beak, the yellow of a buttercup petal—to be lost beneath the abstraction of a testable hypothesis. Somehow, in drawing lines, the edges that exist between one object and another, between me and the world, diminish.

Up here, near Botany Pond, I’ve circled out across the rolling hills and then back towards a narrow string of aspen trees. My truck’s not far. E.B. White—a man immersed enough in the natural world to convincingly write the lessons a spider and a barnyard pig might teach one another—once said that a blank sheet of paper was “more promising than a silver cloud and prettier than a red wagon.” I look down at my page. Its promise has turned into a list of springtime happenings: first flowers beginning to bloom, first bluebirds fly-catching from the lower branches of an aspen tree, last ice still caught in the lee of north-facing slopes. This list is open-ended: one that builds on observations made in years past, one that will call me back to these rolling hills again and again.

The most thoughtful collector I’ve ever known was my professor, the late Wilf Schofield. All collecting, whether it’s acknowledged or not, carries responsibility. Like most botanists, Wilf labelled each specimen with a sequential number that tied each specimen to information recorded in his field book about where and when he had found the plant. Referred to affectionately as a “garbage-bagger,” Wilf was renowned for both the number and sheer mass of his collections. Whenever he could, Wilf ensured that the collections he made were large enough that they could be divided and shared with museums around the world.

Wilf, along with his students, built the collection of bryophytes—the small, nonvascular members of the plant world—at the University of British Columbia into one containing more than 250,000 specimens. When Wilf died in 2008 at the age of 81, his own individual collection number had reached a staggering 128,619. He assigned this last number to a moss he’d gathered in the last summer of his life on an island in the Aleutian Archipelago—just days after the island’s volcano had erupted.

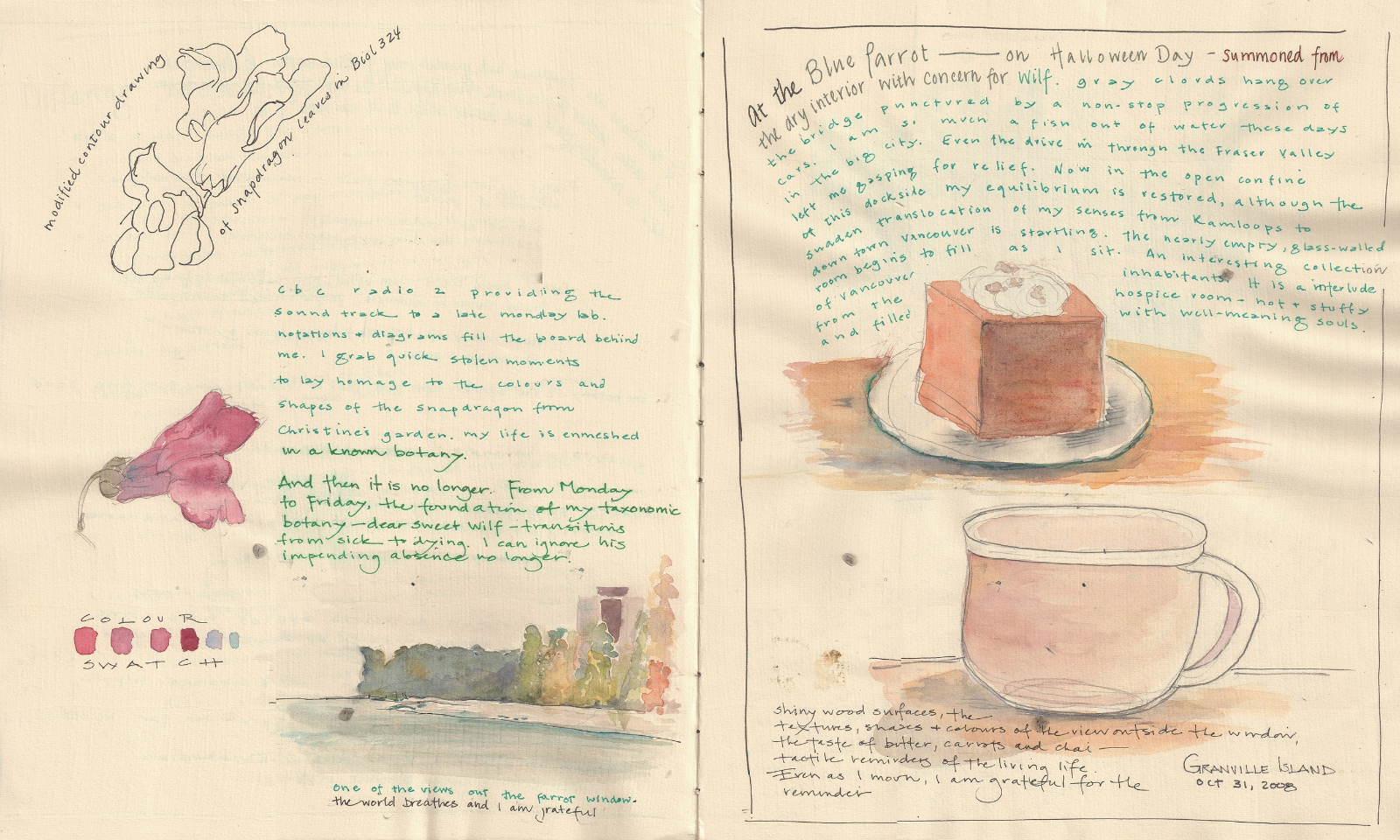

Collections—mosses in an herbarium, paintings in a museum, entries in a field journal—never end (that is, after all, a big part of their lure), but collectors do. When Wilf was diagnosed with cancer, I visited him in Vancouver General Hospital with my husband Marc and my daughter Maggie—Maggie doodling in the back pages of my field journal as we chatted. That day, Wilf was full of plans for what he would do out of the hospital and I refused imagine him anything but whole. A few weeks later, I drove back across the mountains in a rush, afraid I would be too late. I was not the only one. During his final days in hospice, Wilf’s former students came from across North America to stand at his bedside. It was easy, with Wilf gaunt and skeletal in bed, his flesh already disappearing under the burden of too many hungry cells, to worry about Wilf’s collection. To wonder how our collecting would bear the weight of his absence.

When Wilf’s doctor shooed us out of his room saying he needed to rest, I walked a few blocks with a friend—a woman who had helped collect mosses for my own research—and then fled west along the busy streets that separated Wilf’s hospice from the edge of the Pacific. Was it then, I wonder, using my field journal to find solace in the random assemblage of objects observable from a dockside café that I understood how different my collection would become from Wilf’s?

Many collectors apprentice first with ‘things’ different than those that will form the dominant collection of their lives.

Today, I don’t collect as much as I should. Not scientifically. Since finishing my Ph.D., my collecting number has been stalled in the three-digit range. It will be unlikely, I think, to ever exceed four digits. Educational activist and author Parker Palmer wrote, “We teach who we are.” I think the same is true for collecting. We collect who we are. All day, every day. If we’re lucky, our collecting requires the talents we have to give. When the German zoologist and artist, Ernest Haeckel began to investigate the microscopic radiolarians of the Sicilian sea with microscope and paintbrush, he is said to have written to his fiancé that this work was ‘made for me.’ If we’re lucky our collection requires our own direct experience—informed by, but not swamped by others’—of the world around us. Nothing ties us more powerfully to the world’s richness than our own observations.

If we’re truly lucky, the collections we make take time and energy and heart to figure out. A sorted collection is no miscellany; it is a physical manifestation of what we know to be true and important. Yet no collection is without cost. The objects in our collection always come from somewhere. Collecting for experience means that more often than not, I collect like a magpie, distracted by the shiny moments of individual lives: the emergence of a fungus, the opening of a buttercup, the glance of a hawk. None of which can be preserved in a museum. But I think of naturalist Robert Michael Pyle’s question, “What is the extinction of a condor to a child who has never seen a wren?” If nothing else, twenty years of field journaling has taught me to see the wrens.

Maybe it’s not what we collect but what our collection does that matters. In science, ‘collect’ means to gather systematically. In the Catholic and Anglican churches, a collect is a prayer offered up at a certain time. I wonder if both aren’t a kind of listening, a way of attending. Maybe the best collections are those which make us open and porous to the world. And maybe, in the new, unpredictable world of the Anthropocene, listening—whether through specimen or line, worry or joy—is what the world needs most.

Back at my truck, I open the door and sling my pack and field journal onto the bench seat. Driving home, hills roll by on either side. Around one corner, I spot a hawk, perhaps the same one I saw before, spiraling upward. I wonder what it’s hunting. I glance over at my field journal; it’s only a week old, but already its pages are filling. In a couple months, I’ll add it to the stack that sit on my bookshelf.

Tonight, I’ll finish work on a guide to my favorite field journaling exercises for a local art gallery. I’ll share this little guide as widely as possible and will be overjoyed when it’s adopted by teachers far from Kamloops. Inside and outside my university, I will teach field journaling workshops as often as I can. I will not hesitate to speak—at conferences, in grade schools, in my own courses, on the radio—about what the first-hand knowledge of the natural world has to offer us all. I will jump on any chance to cultivate experience, to document today’s baseline of the natural world as richly as possible. I will seize any opportunity to remind myself and others that, here in the Anthropocene, our greatest challenge is to imagine the lives beyond our own. That each time we stop to listen, to draw, to hear, to feel, we give the gift of our attention.

I will treasure my memories of Wilf in the field—bright, yellow rain pants and faded green slicker cloaking his tall frame, worn canvas bag bulging with bryophytes slung over one shoulder, gray-hair pushed awry by wind and rain, numbering up prayers, one by one, for the plants he loved. I will remember Wilf’s collection numbers as marking both individual specimens and moments of hope. I think Wilf, and maybe Douglas before him, listened best depositing herbarium specimens; I know I listen best when the more-than-human world grips me as tightly as a hawk clutches a freshly-killed vole.

Today, driving the last curves of the gravel road home from Botany Pond, I understand that the collection that has allowed me to make sense of my own life, that may well be my most important contribution to place and community, is the line of field journals standing quiet and inert on my bookshelf.

No wonder the current volume comes with me everywhere.