What is it about a wall? About the action of marking or writing on it? What kind of power does it exert on the writer/painter/activist/transgressor, and on the viewer/reader/witness/accomplice? Does it evoke some obscure genetic memory of our cave-dwelling times? Our beginnings as beings without a common language, or in its developing stages, where the magicians/priestesses/rulers were the ones with the power to create form, color, symbol and meaning, with a stroke…

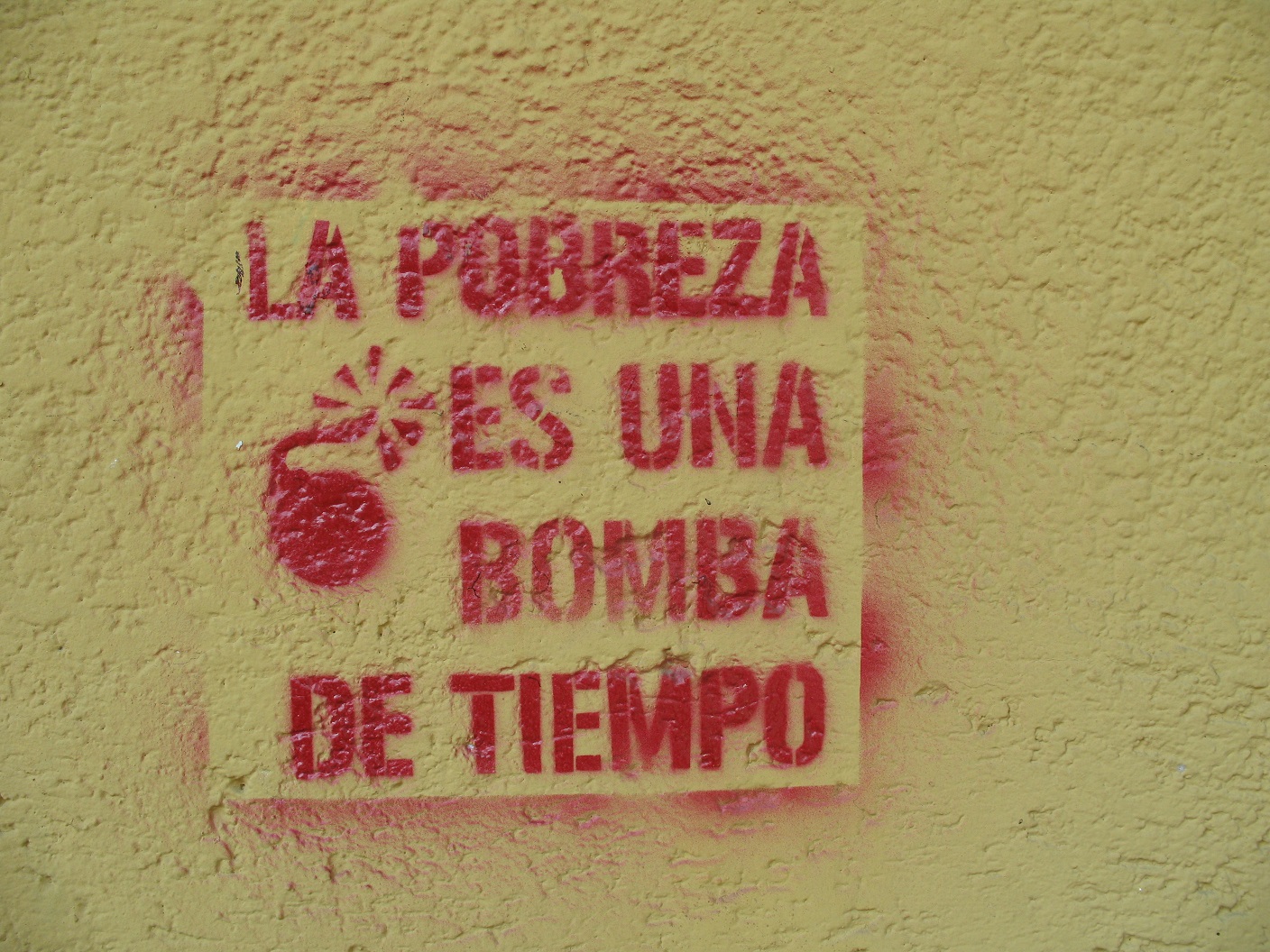

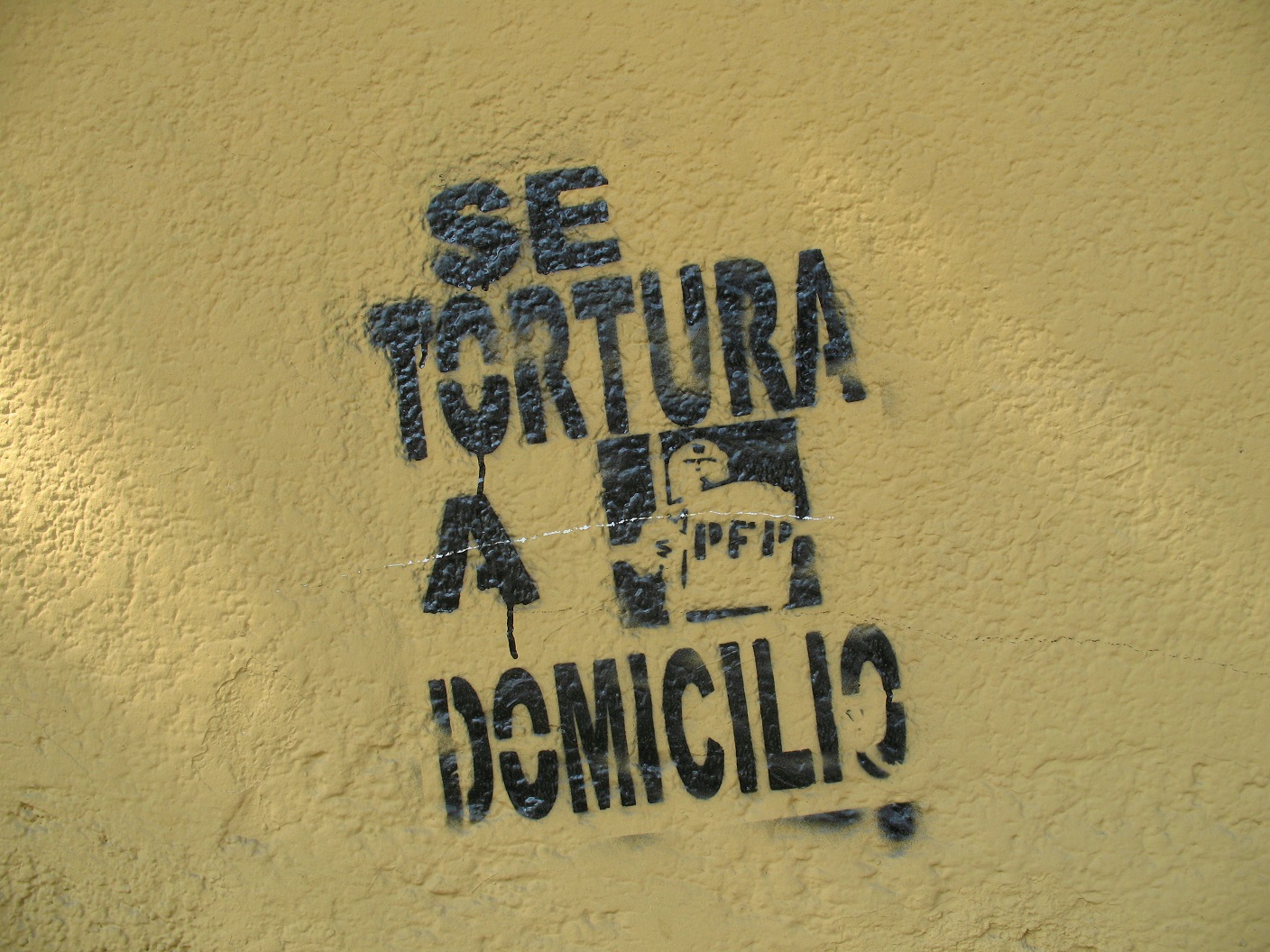

I started to take photographs of mural street art with some regularity after I moved back to Mexico City, in 2005. I lived in the old section of Coyoacán, a few blocks from Frida Kahlo’s famous blue house. A neighborhood where history and culture fuse through the traditions kept alive by the pueblos that still inhabit it, with more bookstores per capita than anywhere else in the city, probably due to UNAM’s closeness; a town within the larger monster of a 22 million people metropolitan area. I specifically took photos of the places I walked by regularly. I didn’t have a plan, just as it has been the case for most of my photographic work; but with the years, it became a reflection of my transient life. A kind of map of my travels and multiple moves, for sure, but more than that, a map to my thoughts, projected on the scribblings of others; my inner hopes expressed by someone else’s need to share theirs in a public space, a political space, a recriminatory and limiting space, a total-lack-of-democracy kind of space, a corruption-is-here-to-stay kind of space. Freedom is messy, but smells so good. The city then was governed by a leftist party for the third period, while the presidency had been robbed in rigged elections and president Calderón’s reign of death was just starting. Artists were trying to warn us…

Even in the eve of some of the most violent times to be seen in our contemporary history, I felt a vibration I hadn’t sensed in the city since I was a kid. For a little while, we, chilangos —the name assigned to those from Mexico City—, trusted we were in good hands. Mexico City was the safest in the country; there was no repression, at least not the one happening at a Federal level. You’d see stickers, sprayed complicated signatures, stencil designs, huge cutouts. The walls, once again, evoked the imagination, allowed for secret messages, private utterances, and, strangely enough, a sense of love and unity, by sharing the public space.

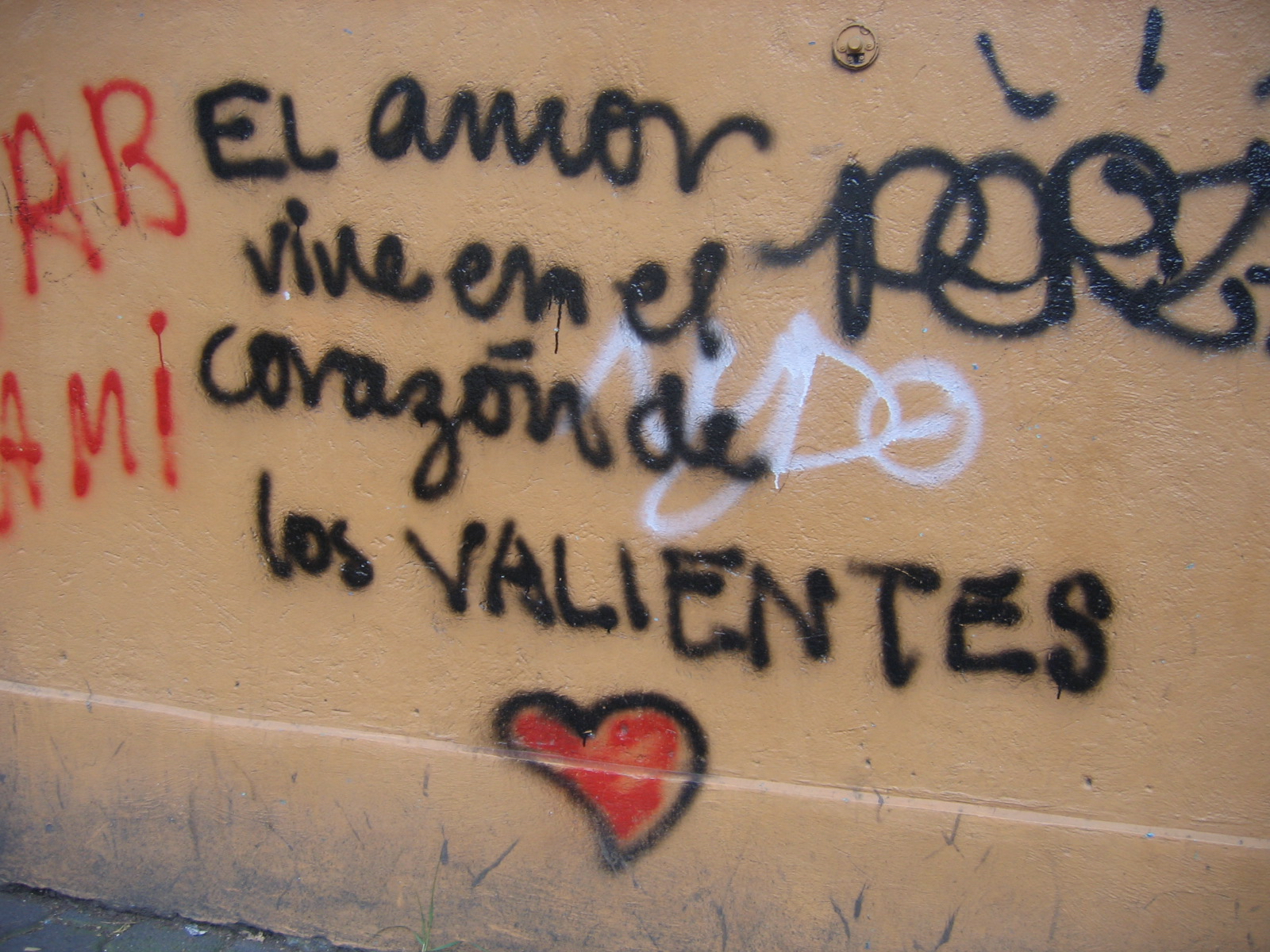

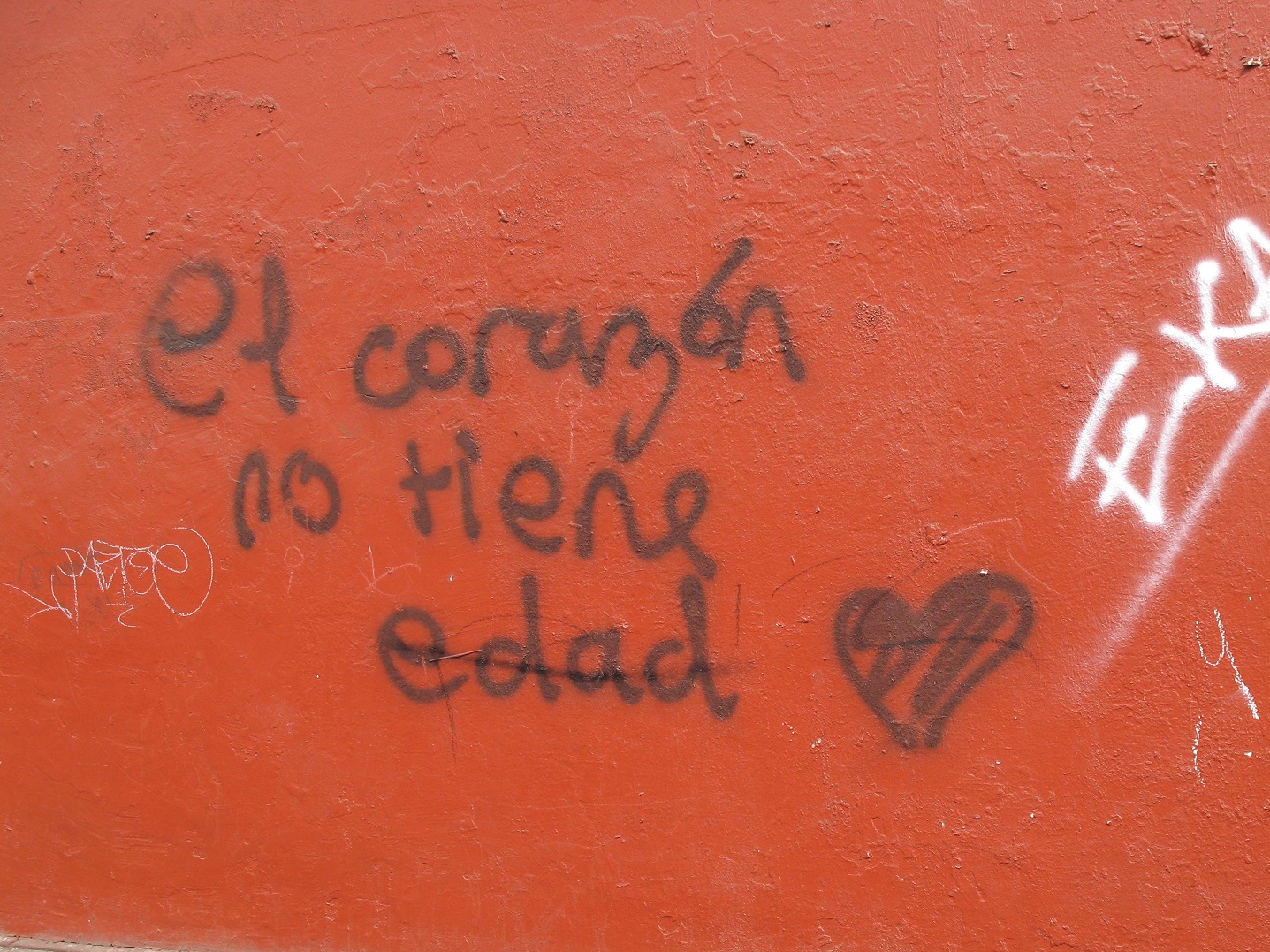

Some of my favorites were those hugely handwritten micro poems on the walls, I must be a closeted graffiti artist of some sort. I don’t write on the walls, but I have shouted my poems in the streets and subway stations. Some might say, That is not art! That is not a political text! And yet, I would say the mere act of writing on a forbidden surface: “Touch yourself and enjoy it,” is a taboo-breaking invitation. To remind us that the “heart has no age” or “love lives in the heart of the courageous,” might not be expressing original thoughts, and yet, to manifest them on a stranger’s wall, is an intrepid act, showing once again that love, beauty, and poetry can also be real acts of dissent.

Of course, some were plain ugly scribblings, but at least they were an attempt to shatter one’s sense of normalcy, they reminded you of some primal force, maybe anger or something more profound, which pushes someone to state their presence in life. The onlookers, before it, become potential retrievers of a thousand stories, reliving ancient times when art was not a commodity, but part of our daily happenings. Beyond their offered protection, walls meant we could be shaken, moved and in-formed, they were our newspaper, our movie screen, the “Internet” of those times.

I once encountered an “art show” right on the street I lived in. All the art was made onsite, with chewing gum. It was set up as a gallery, with labels indicating the names of the oeuvre and artist. I enjoyed the playful commentary on commercial art and its allusion to how alien that whole world is for the passersby, who, I noticed, didn’t care to read them. But even if the result wasn’t the expected one for the infringing artists, no doubt those years were a fermenting moment for me and for the walls in Coyoacán; we were each developing our identity, it was merely a buzz but it was strong, and some were listening. They were attempting to resist

becoming a color-schemed Disney-like-colonial-town (remember Coco?), an exclusive and “clean” looking zone for tourists, rich notaries, private schools, and such. Think about it, this town’s center is older than the “discovery” of the American continent,

founded next to a now dry and long forgotten lake, with formidable trees. Even now, a government-run nursery subsists there. Cortez and Malintzin’s homes, dozens of churches, and narrow cobbled stones are the beautiful trademarks of other troubled times, better left behind, never to be forgotten.

Walls should not only remind us of the past, they should offer visions of a possible future in the present. My time in the city was right before the Occupy movement, and in some areas, it was more than walls what artists were appropriating. Government efforts went to try and channel the youth towards doing their art in a consented space, giving them white walls and free paint, paid by COMEX, a Mexican paint brand. Graffiti and street artists were acknowledged, and were given an opportunity to express themselves, with social purpose. Such was the case of the School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, where two sides of the surrounding wall became the canvas for

a myriad of young artists. I have used eyeglasses since I was eight, so I have always been self-conscious about my sight. I remember the attraction felt every time I’d drive by these works, until I finally walked there and spent one of those glorious Tenochtitlan afternoons —“the most transparent region,” Carlos Fuentes would describe it—, documenting it. It is totally gone by now, which is sad, but such is its transient nature.

Towards the end of those eight years I lived in Coyoacán, street art changed. It was a reflection of the new political life in Mexico. There was a new mayor, a man with no party or ideology. Concert promoters and beer companies started to use street art techniques to publicize events. Cleaning overnight happened more efficiently, and walls started to look empty, smelling of a quiet and disinfected soul. Even its name, which for me had always been el “De-eFe” or D.F., which in turn made me a “defeña,” would never be. My dirty “DeFectuoso” had become a brand, an unpronounceable acronym in Spanish: CDMX.

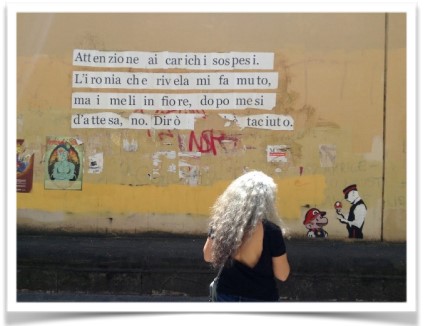

Between 2013 and 2015 I traveled a lot, and street art continued to seize my photographic attention. The purpose of my travels has never been taking pictures of street art, but whenever I encounter it, if there’s a pull, I will click and capture. Some cities’ walls are more inviting than others, they allow for the unexpected. There were some wonderful accidental findings, like the installation of hundreds of make believe dollars on the front of an abandoned factory in Florence. Walking around this Italian City one would start recognizing the same artist or find poems from the same collective. I loved such coincidences, the ludic potential of repetitiveness. To find almost the same image in a different corner, made me feel there was maybe a hidden message, or a story to be continued. At times it felt like I was retracing the artist’s path, getting a bit closer. Will I find her around the corner? Will I catch him the next time? These are just poetic ramblings of course, because it was clear I would never catch a glimpse of the

author/s and that I would remain forever a bystander, which can actually be an important role, given its unavoidable mutating character. All street art will be intervened by someone or something else. Even the act of erasing it is all part of its brief performance, and gives it full symbolism. It is there to remind us, but only for an instant, so then, we need to pay attention, to capture the brevity of its tongue. A wall can be painted and repainted with such ease. It can be white, then black, then blue, rainbow… And yes, a wall, once it’s been converted, it will be converted again, and again. A fleeting and promiscuous canvas. Some might say, No respect! And yet, why don’t we question the commoditization of art itself? The godification of the artist? Street art does that, of course. Its value is based not on some collector or gallery owner’s whims, it is free and shared and momentous. And good or bad, someone will cover or transform it, somehow. A man will acquire glasses and a mustache, and seem not to resemble Passolini anymore, and yet,

the way he carries that young man, his offering posture, his entrega…I take and accept it. This is emotional, and political. This is poetry! I should know.

So, I find myself writing about the writing on the wall, digging in, racking my brains having to choose from works, cities, anecdotes. The map unfolds exponentially, and the corners fall off the side of the table, while hundreds of photos of anonymous expressions are hoping for me to extract them from a multidimensional chest of memories.

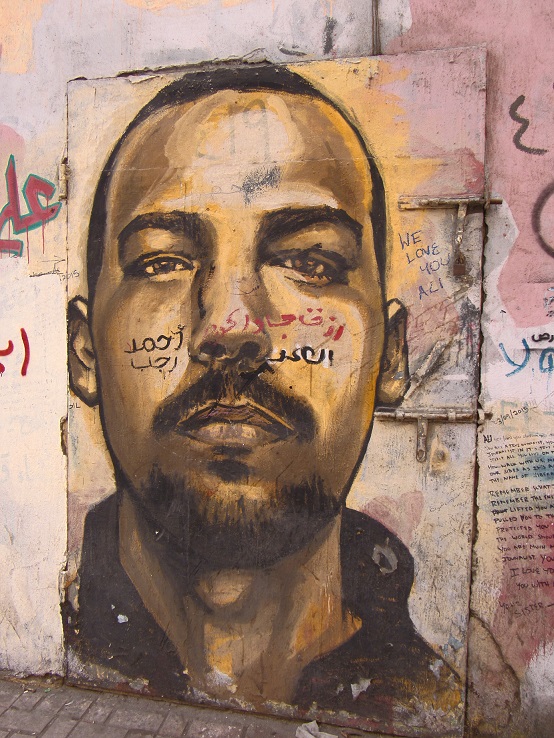

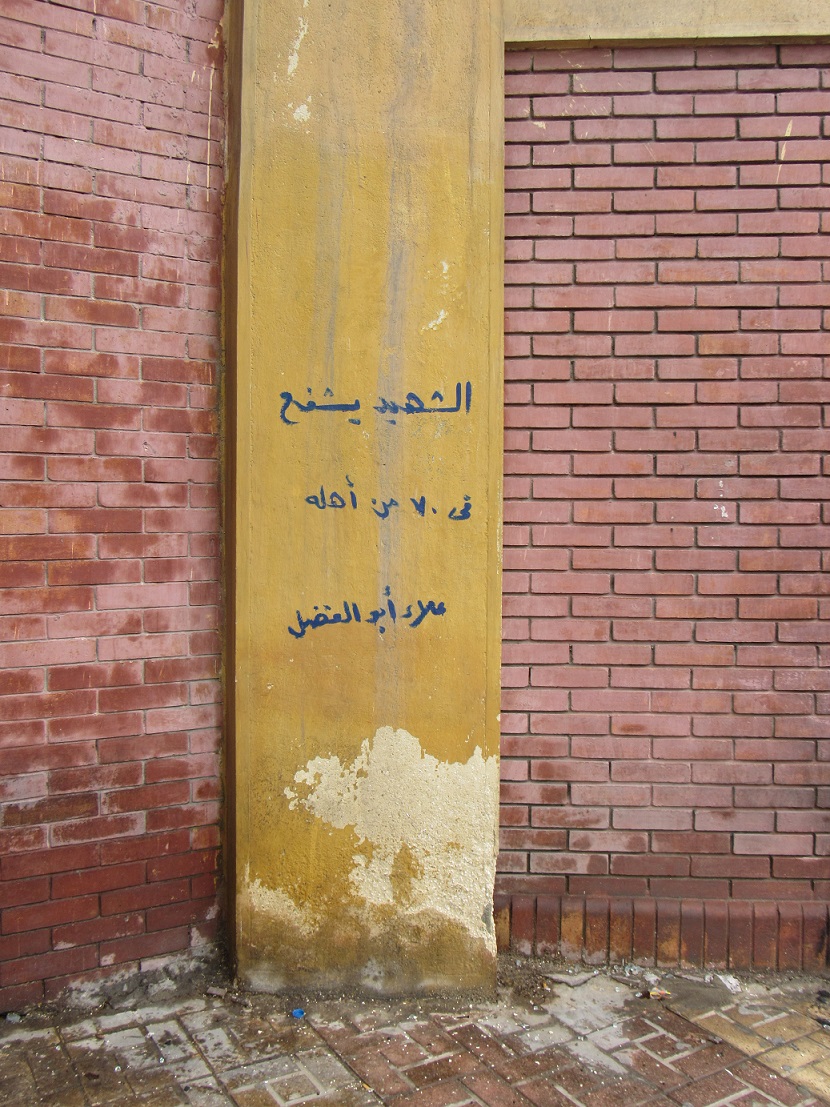

Some of these instants are marked by the limits of memory, but specially, language, like when I visited Egypt. Walking around Tahir Square, in Cairo, I wished for a guide to walk me through the historic narrative before my eyes. I was captivated by the variety of expressions, particularly the beautiful Arabic calligraphy, an art in itself, applied to the walls of the university and other public buildings. My Iberian blood whispered recognition and my Mexican American experience confessed its alienation. The translator needed translation of all that was being said on those walls, so clear to the actual inhabitants of the city. I wondered if I could ever recover my Moorish roots, but, I was again, daydreaming along. And it has been so, whether I am in Rio, or Havana, Quito or Mérida, I bring home with me so many untold stories, unsung poems, mine and the ones I’ve absorbed, admired, sucked in through form, color, and texture. As in all expressions, whether it’s artistic, or simply human in its multitude of possibilities, all of us, creator and re-creator, audience and intervener, react to the tactile and visual experience, receiving unconscious messages others will decipher. That is our future history.

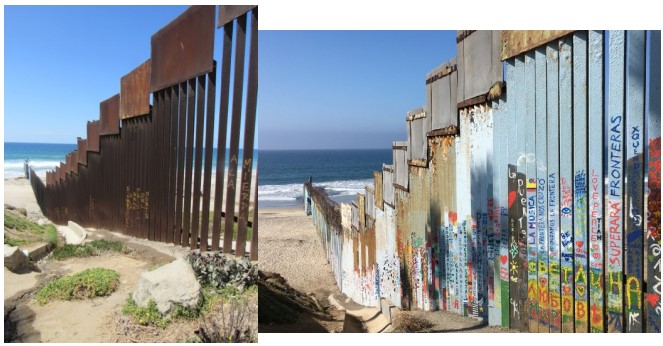

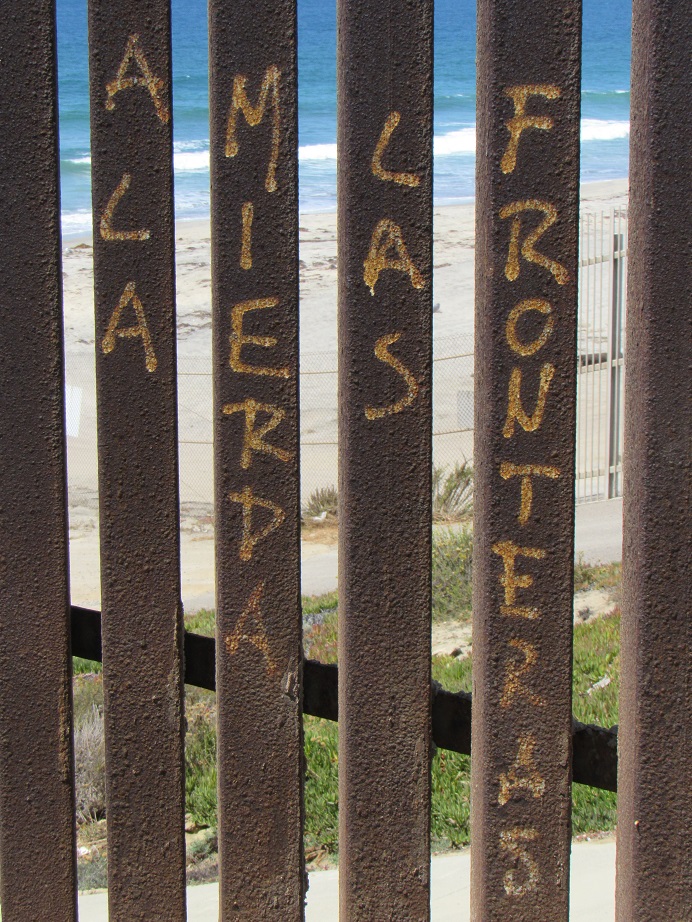

When I moved to Tijuana in 2016, at the beginning I didn’t see much street art, but then I started to find it everywhere, mostly while driving. It was easy to walk in Coyoacán and re-discover details, a sticker here, a painted LP on the post above, those kind of changes, overtime; it was a microcosmic search of sorts. In Tijuana, it’s all about murals. It is a difficult city and a lot of the mural art is dispersed all over the metropolitan area and on columns and walls holding underpass bridges. One of the exceptions is the so-called Parque de la Amistad, in Playas, right where Ia patria begins and the border wall ends. Yes, The Wall itself, the one president Trump would like to take credit for (while charging us Mexicans for it), except a large segment was already there before him. In any case, I’m talking specifically about the section ending in the Pacific ocean.

Before Covid, Tijuanenses would spend their Sundays in Playas. In fact, it resembles Coyoacán in that sense. Weekends are crowded with local and foreign tourists, music, food, families, joy. I live in the East side of TeeJay and going to Playas means a 40 minute drive (and then coming back before everyone else to avoid traffic), so it’s not something we at home choose to do often. However, when friends come to stay, it is a visita obligada, one of those places every visitor has to go. So every return, I look forward to the newest mural, or the latest intervention done to a previous one. In truth, “The Wall” really is more like a huge fence, and it doesn’t evoke any of the feelings I have shared above. It is not an inviting canvas, not even a flat surface. The metal and pattern are fascinating, yet they also remind me of jail. It’s the only touristic site I can think of, that I’ve been to, where public art is not only tolerated, it’s expected to be found.

A necessary escape valve, cause otherwise, what would we do with our sense of rebellion and indignation? What would we do with that ugly reminder? How can we get rid of that ugly metallic blinder?

Some years ago there was a famous intervention on it. A Chicana artist painted one section of the border wall in such a tone of blue that, when seen from a certain angle, the wall seemed to disappear. El muro here represents the opposite of the wall in the cave, as it is a barrier, separating brothers and sisters. In this particular corner of the world, street art takes on a different face because of it, identities are clear: depends on what side you’re on. It is called the Friendship Park because a lot of events are organized with the border wall in between the people, dancing and singing jaranas, reading poetry and manifestos. More than 30 years ago, a huge wave ate part of the road and many buildings close to the ocean; then came violent times, followed by very dry ones, when most of the mafiosos left Playas. You can still see traces of all these epochs, but it is rapidly changing. Just like in Coyoacán, public art on the Mexican side of the border wall gives you a sense of how quickly our societies are transforming. Now, there is a small open forum for performing artists, although you’ll find many bandas playing for the picnic-ers on the sand, and along the attractive boardwalk there is an ever changing display of temporary murals and other art forms.

Conclusion seems an impossible task given the inconclusive quality of the project, this map of my life, the one hundred thousand mirrors/screens/murals I have encountered, how hard to leave most behind. I have told you so little. Choosing the photos was a huge task in itself, and ekphrasis can go on infinitely for just one of them, if it awakens such drive! Artists sometimes seem to be mere note takers, but that is one of the most important parts of our process as creators, bearing witness…However, the processes continue, and after the on-looking comes the reflection and the digestion, the regurgitation of a reaction, a grunt, some kind of answer, which necessarily turns into a hundred more questions. We —sentient beings— are constantly tracing each other’s path, following and emulating each other, leaving behind our own tracks, and then learning to read them, messaging is our thing. Like walls, there’s something about the limits —of memory, of space, of language— art is our ticket to freedom, and street art makes it available to all.

So, be welcoming and pay attention to the silent scream, the straightforward note, or the urgent reminder that someone has been brave enough to draw/write/compose/expose purposefully, drawing from her/his place of vulnerability to leave us, yet another poem on the nearest wall.

Tijuana, BC, MX, September 10, 2020

Photo credits:

All photos by Pilar Rodríguez Aranda, except the one in which she appears, taken by poet Edwing “Canuto” Roldán.